Equity and Innovation Report

Chapter 5: Voices of Cambridge

The community speaks out about the changes in its city

Tracy Chang (center), owner of Central Square’s Pagu, is one of many food heroes in the community who are addressing hunger during the pandemic. Photo by Lou Jones.

Tracy Chang (center), owner of Central Square’s Pagu, is one of many food heroes in the community who are addressing hunger during the pandemic. Photo by Lou Jones.

Cambridge is now a part of the wave of innovation cities whose booming economies, based on investment in research and advanced technologies, are changing the way people live. The city’s vitality has been a blessing, generating growth, increasing incomes, bolstering municipal finances, and conferring an enticing appeal. But it has also created challenges by driving up the cost of living, decreasing housing affordability, and diminishing the sense of community as long-term populations are displaced by newcomers who may lack a sense of history and connection.

Many people who grew up in Cambridge and feel a deep attachment to the city cannot afford to raise their own children here.

In putting together this report, the Cambridge Community Foundation spoke with nearly two dozen people who live, work, study, or worship in Cambridge — people from all walks of life and all income brackets, and representing many races and ethnicities. Their words point the way to common and conflicting values, ideas, and points of view that can and should spark a much-needed civic conversation. We share some of their voices here.

Income Inequality

In this new Cambridge inequities abound. More children reside in wealthier households than a decade ago, but a third of single-parent families are in the lowest-income quintile. Seniors, too, are highly income-polarized, while the young-adult workforce comprises the middle- and upper-income tiers.

The plight of residents living on the edge, with incomes a fraction of those enjoyed by high earners, has steadily worsened as the city has grown more expensive around them. The data lay bare the economic fragility of so many households and underscore the correlation of race and ethnicity with income.

Poverty and prosperity are sometimes separated by just a few blocks. Many of the residents we spoke with noted the need to support our most vulnerable populations, challenging the city to make equity, inclusion, and justice not only words we say but actions we take as a society. People see diversity in experiences, races, and cultures as critical to the alchemy that leads to innovation and to a sense of community. Several of our interviewees mentioned that high rents are pushing out not only residents but also mom-and-pop stores. Said one, “A city loses a lot of its character when everything is high-end.”

Many also noted the dwindling of the middle and artist classes, emphasizing that reinvesting in both will help to keep the “feeling of possibility” that has always existed in Cambridge. “All the artists I know have had to leave, including even my parents, who had been here since the ’70s,” said one woman, a classical musician. “I’m lucky because I have this co-op, but I also feel so alone. It’s me among the doctors.”

That feeling of invisibility was not uncommon. “A lot of the wealthy don’t realize how much poverty there is in the city, because they’re living in such isolation,” said one woman, a retiree.

Tony Clark of My Brother’s Keeper Cambridge has been one of many local advocates for the Black Lives Matter movement. Photo courtesy of My Brother’s Keeper Cambridge.

Housing Affordability

A place to live, a path to wealth formation. There was a time when America strove to correct housing inequities, but its solutions were far from perfect. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, a bold and sweeping response to the Great Depression, included a big push toward home ownership in the form of legislation and mortgage support, but it also ushered in public housing, which would develop problems of its own as the years wore on, and discriminatory practices that encouraged racial segregation.

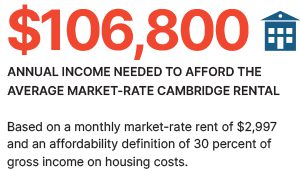

Still, ownership and the wealth-building that went with it gradually increased for all races and classes — some more than others — over the next half century, before spiking in the late 1990s and early 2000s in a bubble that burst disastrously for millions of lower-income homeowners. Unfortunately, prices didn’t decrease enough after the 2008 crash that home ownership opened to a new generation — and, they’ve risen astronomically since then, making Cambridge a city of renters.

Regarding the impacts of growing inequities in a high-cost city, folks are disheartened by the lack of options: “Things are being built left and right, but it’s not something just anyone can afford,” one said. “Who is Cambridge for now?”

Some of our interviewees looked back with nostalgia to the 1970s, when rent control, which ended in 1994, “allowed us all to live amongst each other,” according to one man. “Black families were able to live on these nice tree-lined streets. All of those folks had to leave.” The Cantabrigians we spoke with bemoaned the loss of community and recalled neighbors who had to move out as prices rose, leaving them without a “network of people you can trust.” They expressed concerns about high costs driving out so many who have made Cambridge their home for decades. “We’re still diverse,” said one Black businessman, “but most of the diversity lives in the projects or in low-income housing, so it’s segregated diversity.”

“Many of our kids walk among the tech and university buildings and have no idea what’s going on within them. We need to do a better job of planting the seeds to guide our young people towards career paths within the innovation sectors.”

— Ty Bellitti

Education Inequities

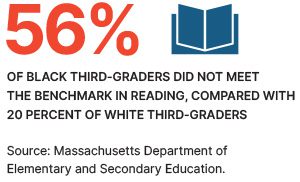

Persistent racial disparities begin early. Cambridge is a higher education and innovation mecca, with the highest share of adults with advanced degrees among the 25 innovation cities. Yet its racial disparities in education are stark and persistent, and the city is unable to retain young Black populations.

Compared with other groups, Black Cambridge residents do better than the state average for their peers, with 33.5 percent holding a bachelor’s degree or higher, but not as well as other racial groups in Cambridge.

The imbalance begins in K–12, where the city’s income polarization is reflected in its racial makeup and in where the children live. Though Cambridge’s public schools have the state’s second-highest per-student expenditure, racial inequities remain. As the country in general and Cambridge in particular move away from an industrial economy and toward a world of innovation and high tech in the fields of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math), these inequities are even more life-altering than in the past.

Residents commented extensively on this topic. “A lot of very inflamed, explosive issues come up around the schools,” said one, “but my frustration is with our failure to do the deep, thoughtful, creative work that’s required to level the playing field — generating more opportunity and strengthening the academic, career, and life prospects of all kids.” STEM initiatives, according to a city employee, are “trying to create pathways, but we’re up against the powerful cultural reality of institutional racism. There’s been an awakening recently that the status quo — patting ourselves on the back and saying we’re doing well relative to everyone else — is not good enough.”

She wasn’t the only one to link education inequality to a larger problem: “Racism is America’s great flaw,” said a local business owner. “It’s been there since the beginning. America will never be what it promised, the aspirational parts of our history, until we reckon with that legacy, and Cambridge is not free of that — it’s there structurally in the school system, the police force, city government, and in many of society’s private, business, and civic institutions.”

Tina Alu prepares to open the Cambridge Economic Opportunity Committee’s food pantry. Photo by Lou Jones.

The Pandemic

The long-term impact of COVID-19 on communities will not be known for a while. The disparity gaps were widening well before Cambridge was dealt the additional blow of the pandemic in early 2020. In a matter of weeks, job losses and unemployment applications skyrocketed; beloved restaurants, cafes, and small businesses closed, in some cases permanently; layoffs and furloughs decimated “recession-proof” industries like higher education; and the closing of schools revealed that four decades since the start of the computer revolution, a digital divide still exists — even in a city that is home to many of the largest tech companies in the world.

If there is a silver lining to the pandemic perhaps it is the clarity with which inequalities have been laid bare and the opportunity that affords us to take decisive action for positive change. Innovation cities like Cambridge are shaping the future of urban America, and their decisions today will determine whether the benefits of the new economy will be concentrated at the top of our society or shared more equally among all residents.

We asked people how the pandemic affected their lives and what they thought its fallout might be. “Everyone is paying attention [to racial disparities] right now,” said one Cantabrigian, “but will they be paying attention later? Will this interest and care continue? How real will it be for people in this city in the long run?” Others suggested a more concerted effort to create community events like block parties to help neighborhoods rebuild once the crisis is over. “We took community events for granted when everyone was able to go out and move around,” he said. “But now we’ve had the wake-up call that we have to rebuild together.”

One Harvard professor summarized the feelings of many when he said, “I want desperately for this pandemic to be a catalyst for change. I have often hoped that the pandemic would bring home how uneven the playing field is for low-income people and communities of color and would motivate people to walk the talk and mobilize for far deeper, more meaningful change.”

Yvonne Gittens, a lifelong Cambridge resident and longtime volunteer with the Cambridge Community Center. Photo by Lou Jones.

A Sense of Hope

A flawed but much-loved community looks to the future. Cantabrigians often say that their city is a special place — an intersection of education, innovation, and art with a certain openness and freedom, threaded together by humanistic traditions and a generous attitude. Many believe we have reached a critical juncture where we must contemplate the future of our community, seize the opportunity — and fulfill the obligation — to think differently about our city and the challenges we face.

Residents repeatedly highlighted the possibilities in a city that is deeply intellectual and where “values of academic excellence and self-improvement trickle down to all so that people from Cambridge want to aspire to greatness,” despite the fact that many “slip through the cracks because we rest on our laurels as a city.”

Cambridge’s manageable scale, innovation mindset, and deeply held values of equity and inclusion are important assets for making change — perhaps even change that can act as a model for other innovation cities. We have the resources and the capacity to build a better and stronger social, civic, and economic fabric for an inclusive future, and to design the city we all want to live in. The people we interviewed pointed out that the city has good resources for immigrant families, supports local “nonfranchise businesses,” and has a “good number of outdoor spaces and green areas to escape to.” People appreciated its “inclusionary housing,” its being “a leader in participatory budgeting, recycling, curbside compost pickup, and other everyday conveniences,” and the “collectivist experience” of politics here. “It’s not perfect by any stretch,” said one man, “but it’s the only place I’ve lived in my entire life where I truly felt like I belonged. When I get up in the morning, I’m pretty excited to be here.”

A Call to Action

This report is a call to action. As a community foundation, we see a Cambridge that is generous, concerned, and resourceful. We are relying on those altruistic impulses to guide us through the coming years to a more equitable future for all Cantabrigians.

To that end, the Cambridge Community Foundation will invite dialogue among stakeholders across city sectors and work to make these discussions a catalyst for developing an inspired, inclusive agenda for the city we love. We call upon community leaders from all disciplines to join in shaping this transformative discussion. Our beloved community is wise, experienced, angry, insistent, and determined. Its voices are not to be ignored. We must listen to one another, and, together, take action.

More Voices of Cambridge

“When I grew up in Newtowne Court, there was a community arts center and we did pottery, darkroom photography, crafts, rap, musicals. We were poor, but we were so rich in experiences due to the center. And through the mayor’s program and the workforce program we learned things that to this day help us — resume writing, interview tips, teamwork, and a work ethic. We didn’t realize how important it was until later on.”

— Emmanuel Mervil, Food Consultant

“I feel like there’s great opportunity in this terrible pandemic — an opportunity to take a step back and figure out what was working, what we miss, and what we can live without.”

— Jim Manning, Magician

“We need to stay vigilant and continue this charge forward to really create equality in our city. … We have a lot of work to do and there are a lot of young people’s lives at stake.”

— Rose Schutzberg, Medical Student

“People should be able to live without the fact of their economic status demeaning them.”

— Polyxane Cobb, Retired

We have adjusted the standard naming conventions established by the U.S. Census Bureau in the following ways: “Hispanic/Latino” ethnicity is referred to as “Latinx”; “Black” refers to “Black/African American”; “Asian” includes “Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander”; “Multiracial” refers to “Two or More”; and “Another race/AIAN” includes “Some Other” and American Indian/Alaska Native.” For more about our terminology on race and ethnicity »