Equity and Innovation Report

Special Focus:

The State of Black Cambridge

The impact of the innovation economy on a long-established community

Shirley Harvey, a life-long Cambridge resident and leader in the community, with her granddaughter Jada. (Photo by Kristen Joy Emack)

of Black households are renters

Black residents has lived in their home for over a decade

Less than 5% of Black adults work in the innovation economy

Black people have lived in this city since the late 1630s, when Cambridge was the “New Towne” across the river from Boston. Many were enslaved in Massachusetts until 1783. But the story of Black Cambridge is not simply about slavery; it also includes interaction and cultural exchange with Indigenous people. By the time the Civil War was over and the rest of the country had caught up with abolition, a Black middle class had emerged in Cambridge that included educators, businessmen, lecturers, and authors, as well as everyday residents who were building community through their churches, select small businesses, and fraternal orders like the Elks and Masons. An extraordinary — for the time — number of African Americans held appointed or elected positions, including common councilors, the fire chief, a city medical officer, a U.S. attorney, and others, from the 1870s through about 1900, when machine politics geared up and Woodrow Wilson segregated the federal service.

At the turn of the 20th century, Black Cantabrigians were part of an emerging middle class and contributed to a strong sense of community. Photos courtesy of Cambridge Historical Commission.

By the 1920s, Black residents — consisting not only of African Americans but also a large influx of Barbadians and Jamaicans who came seeking jobs — made up nearly 5 percent of Cambridge’s population. They resided largely in the lower Port neighborhood, in Central and Porter Squares, and along Walden Street between Richdale Avenue and Mead Street. The ensuing decades brought disruptive government-enforced housing segregation, including the 1938 razing of a low-income tenement neighborhood. In its place, two low-income housing developments were built side by side in the late 1930s to early 1940s, and they practiced segregation in housing assignments, with Newtowne Court primarily for white and Washington Elms for Black residents. As for the practice of redlining — the Federal Housing Administration’s refusal to insure mortgages in or near African American neighborhoods — it isn’t clear whether this widespread practice had as damaging an effect in Cambridge as it did elsewhere. In fact, Black home ownership was relatively high for a time, with many middle-class Black families owning their homes and establishing strong communities especially along Western and Concord Avenues.

Highlights of a Decade of Change in Cambridge’s Black Community »

Home Ownership and Security

Policies that hampered home ownership in the past — along with dramatically rising prices since the turn of the 21st century, which motivated some longtime residents to sell and often prevented new middle-class Black families from buying — are key impediments to the long-term economic security of this significant group of Cantabrigians. Today, about 20 percent of Cambridge’s Black population are homeowners, as compared with nearly 36 percent of all residents. Of the city’s 16,529 owner-occupied housing units, about 6 percent are owned by Black residents, while a whopping 79 percent are owned by whites. In addition, disparities in K–12 educational outcomes suggest continuing limits on Black participation in an economy that demands high levels of education. The community is further hampered by the declining numbers of those aged 17 to 34, who will dominate the city’s future workforce. Black participation in Cambridge’s innovation economy remains lower than that of other demographics, and as a consequence, this group has seen little benefit from the developments that constitute the “new Cambridge.”

Simultaneously, there are those who are succeeding, as evident from the Black middle-quintile and modestly increasing upper-quintile populations — which raises important questions. What is working for those who are succeeding? How it can be replicated? And what must we do to ensure that all children are equipped to remain in Cambridge as part of this booming innovation economy?

A closer look at the state of Black Cambridge today — at people, families, and households and their access to the benefits Cambridge offers — reveals how recent economic gains and losses have altered this long-established community.

People and Households

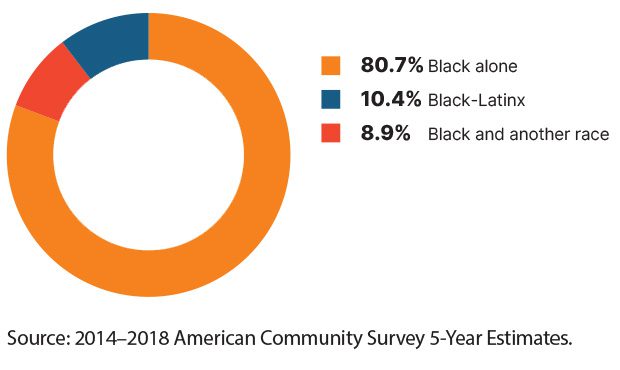

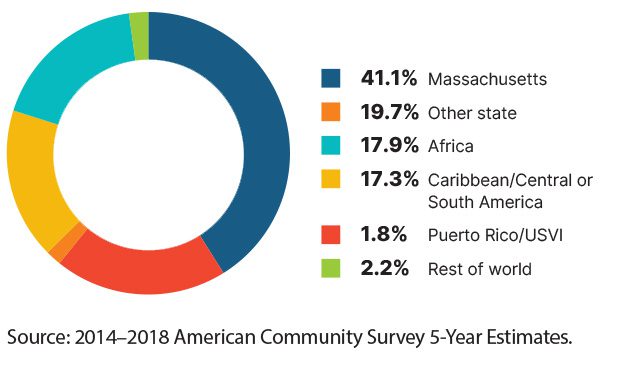

Black Cambridge itself is ethnically diverse; while more than 80 percent of the people in this group identify as Black alone, 10.4 percent identify as both Black and Latinx, and 9 percent as “multiracial, including Black.” Moreover, about 37 percent of Black Cantabrigians were born outside of the U.S., coming mostly from African, Central American, and Caribbean nations.

Compared with the city as a whole, Black Cambridge1 is underrepresented in the core millennial demographic. While 18- to 34-year-olds comprise nearly half the total population of Cambridge and account for almost all of the growth, just 10.5 percent of that group and 8.4 percent of 25- to 34-year-olds identify as Black.

Compared with just 43 percent of all Cambridge households, nearly 53 percent of all Black households consist of families, as opposed to roommates, unmarried couples, or individuals living alone — higher than any other group. However, 31.5 percent of Black families with children are headed by a single parent — more than three times the rate of families citywide.

Leyah and Kayla Bernard and Apple Emack. Photo by Kristen Joy Emack.

Chart SF.1: Cambridge’s Black Population by Detailed Race/Ethnicity

20% of Black Cambridge residents are multiracial/multiethnic.

Chart SF.2: Black Cambridge Residents by Place of Birth

59% of Black Cambridge residents were born outside of MA.

Chart SF.3: Foreign-born Cambridge Residents by Race/Ethnicity, 2018

More than 37% of Black Cambridge residents are foreign-born, higher than the citywide average.

Chart SF.4: Cambridge Age Groups by Race/Ethnicity, 2018

Cambridge’s school-aged children 5 to 17 years old are the most racially and ethnically diverse.

Chart SF.5: Black Population as a Share of Age Group

25.6% of school-aged children are Black.

Housing and Community

Like all Cambridge households, the vast majority of Black households consist of renters. However, as the Black population of renters declined, the share of households that are owner-occupied increased from about 11 percent to just over 20 percent, while most other racial groups remained the same.

Black residents are among Cambridge’s longest-term residents. More than a third have lived in their current home for a decade or more, as compared with a quarter of non-Latinx white, 16 percent of Latinx, and less than 10 percent of Asian residents.

Cambridge’s Black community has significant housing stability, deep roots, and long-term investment in its city. It has the lowest rate of newcomers, with just 11 percent having moved into their current home in the past year, compared with 24 percent of white, 31.5 percent of Latinx, and nearly 35 percent of Asian residents.

Among both renters and owners, Black households are Cambridge’s most cost-burdened. Nearly a third of Black homeowners pay more than 30 percent of their income for housing, compared with 21 percent of white, 19 percent of Latinx, and 13 percent of Asian homeowners. More than 55 percent of Black renters pay more than a third of their income toward rent, compared with 47 percent of Asian, 42 percent of Latinx, and 35 percent of white renters.

Chart SF.6: Share of Households with Children Headed by a Single Caregiver, 2018

Nearly one-third of Black households with children are headed by a single adult, more than any other group.

Chart SF.7: Housing Tenure by Race/Ethnicity

80% of Black households are renters.

Ty Bellitti. Photo by Lou Jones.

“Unfortunately, I am probably one of the very few people of color that grew up in Cambridge in the ’70s and ’80s who was fortunate enough to buy a home here. None of my friends live here and that’s mostly due to the issue of affordability.”

— Ty Bellitti, Local Business Owner

Chart SF.8: Length of Time Living in Current Home by Race/Ethnicity, 2018

Cambridge’s Black households have the highest rates of long-term housing stability.

Chart SF.9: Share of Residents Living in Current Home for 10 Years or More, 2018

1 in 3 Black residents have lived in their home for over a decade.

Education and Workforce

Perhaps nowhere is the equity gap more pronounced than in educational attainment. A full 80 percent of Cambridge adults hold at least a bachelor’s degree and more than 60 percent hold a master’s or higher. And yet, among adults aged 25 to 64, just over a third of Black residents have a bachelor’s degree or higher. More than 44 percent have a high school diploma or less, compared with 26 percent of Latinx, less than 10 percent of white, and less than 5 percent of Asian adults.

Disparities in education credentials translate to a striking gap in access to the innovation economy. While 22 percent of working-aged Cambridge residents are employed in innovation-related occupations, just 4.6 percent of Black Cantabrigians are — a far lower rate than the 13.7 percent for Latinx, 20.6 percent for white, and 30.6 percent for Asian residents.

Chart SF.10: Educational Attainment by Race/Ethnicity, Adults 25 Years and Older, 2018

33.5% of Black adults have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Chart SF.11: Share of Working-Age Adults Employed in Innovation Occupations by Race/Ethnicity, 2018

Less than 5% of Black adults work in the innovation economy.

Longtime Cambridge resident Susan Richards. Photo by Lou Jones.

“Children can lose hope very young when expectations of them are low. Our white supremacist culture is full of messaging that our children see and feel. Cambridge fails to welcome or prepare Black and brown children for AP Classes.”

— Susan Richards, Fifth Generation Cantabrigian

A Time for Change: The Future of Black Cambridge

The future of Black Cambridge, and the future of Cambridge as a whole, will be determined by how well our children fare. In many cases, the patterns of inequities mirror those that have played out citywide over the past decade.

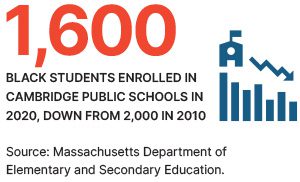

Cambridge’s Black student population has declined as a share of total enrollment. Over the past decade, enrollment in Cambridge Public Schools has grown by 20 percent — from 5,950 in 2010 to 7,091 in 2020. But in that same period, the share of students who identify as Black fell from 33.6 percent to 22.6 percent, suggesting a population in decline.

Chart SF.12: Black Cambridge Public Schools Enrollment, 2010–2020

23% of Cambridge Public Schools’ students are Black.

Chart SF.13: Cambridge Public Schools Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity, 2010–2020

CPS now enrolls more multiracial and white students than a decade ago.

Ashley Herring’s blackyard, a co-op for Black and multiracial youth in North Cambridge, is a place where youth can learn and lead through art, discussion, and mentoring. It is one of many after-school programs that support the success of Black youth. Photo by Lou Jones.

Racial/ethnic opportunity gaps persist throughout the K-12 education pipeline. There is a persistent gap among students meeting or exceeding grade-level expectations. In third-grade reading, 44 percent of Black students achieved benchmark MCAS scores, meaning they met or exceeded expectations for their grade level, compared with 59 percent of Latinx students and 80 percent of their white and Asian peers.

By eighth grade, the opportunity gap widens, with 29 percent of Black students meeting or exceeding expectations in math compared with 38 percent of Latinx, 72 percent of white, and 76 percent of Asian students.

The pattern continues in high school, with 28 percent of Black students meeting or exceeding expectations in English language arts and 34 percent achieving this benchmark in math, compared with around 60 percent of their peers.

Cambridge Public Schools Share of Students Meeting or Exceeding MCAS Benchmark Scores by Race/Ethnicity, 2019

Chart SF.14: Third Grade Reading

Third Grade Reading Average: CPS: 68%; MA: 56%

Chart SF.15: Eighth Grade Math

Eighth Grade Math Average: CPS: 55%; MA: 46%

Chart SF.16: 10th Grade English Language Arts

10th Grade ELA Average: CPS: 62%; MA: 61%

Chart SF.17: 10th Grade Math

10th Grade Math Average: CPS: 61%; MA: 59%

Gaps in college readiness, enrollment, and completion point to long-term racial equity gaps in Cambridge. The logical outcome of the K–12 achievement gaps is that college is not equally attainable by all. Overall participation in advanced placement (AP) courses — a key indicator of college readiness — among Cambridge Rindge and Latin School (CRLS) students has grown over the decade. In 2009, 176 students at CRLS, the only traditional public high school in the city, took AP tests; by 2019 that number had more than doubled, to 433, with a marginal increase in the number of Black CRLS test-takers. However, just under half of Black test-takers scored 3 or higher, translating to potential college credit, compared with 72 percent of Latinx, 74 percent of Asian, and morthan 88 percent of white test-takers.

If education is the great equalizer, the current gaps in college readiness, enrollment, and completion among Black students in Cambridge are of particular concern. They point to the need for additional education support if today’s children — many of whose families have been in Cambridge for many generations — will be able to live as adults in the city where they grew up.

Google and Facebook partnered with the Cambridge Community Foundation to put laptops into the hands of low-income students and workers through the Tech-cellerate program. Photo by Romana Vysatova.

Chart SF.18: Cambridge Rindge and Latin School AP Test-Takers by Race/Ethnicity, 2019

40 of 433 CRLS AP test-takers were Black students.

Chart SF.19: Cambridge Rindge and Latin AP Test-Takers Scoring 3 or Higher, 2019

Nearly half of Black AP test-takers scored a 3 or higher.

Chart SF.20: Cambridge Rindge and Latin School Class of 2011 Cohort Six-Year Post-Secondary Outcomes by Race/Ethnicity

Fewer than 30% of Black and Latinx graduates obtained a post-secondary degree six years after graduating from CRLS.

Tevin Charles (left) with Julio Alexander and Toni Mekhi. Photo by Niko Suave.

Black Talent is Moving Out of Cambridge

When he was in sixth grade, Tevin Charles’ teacher jokingly advised him to buy property in Cambridge right away if he wanted to live here when he grew up. Last year, when he turned 25, he left the Port neighborhood, where he had been born and raised, for California and a more manageable cost of living.

There he found a market for his successful clothing line, Yungsurfgod, and for the skills in videography, audio engineering, and podcast recording he had picked up at the Loop Lab, a Central Square nonprofit.

But home is home, and with his first child just born, Tevin has come back. He says he sees two Cambridges today — “the new Cambridge of high-rise buildings, tech companies, and tech workers, and an old Cambridge that is invisible to newcomers and is rapidly disappearing.”

He’s working in Cambridge now but still can’t afford to live here. Tevin is one of many examples of talented Black youth who have become successful and moved out over the decades. We’re losing the next generation of Black homeowners, civic leaders, business owners, educators, and role models in our community.

We have adjusted the standard naming conventions established by the U.S. Census Bureau in the following ways: “Hispanic/Latino” ethnicity is referred to as “Latinx”; “Black” refers to “Black/African American”; “Asian” includes “Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander”; “Multiracial” refers to “Two or More”; and “Another race/AIAN” includes “Some Other” and American Indian/Alaska Native.” For more about our terminology on race and ethnicity »

Footnotes

| 1 | Because in this Special Focus we have expanded on the standard U.S. Census racial category “Black/African American” to include the population of residents who identify as Black alone and as Black in combination with another race or Latinx ethnicity, these figures may differ slightly from those in other chapters. |