At the turn of the 20th century, Black Cantabrigians were part of an emerging middle class and contributed to a strong sense of community.

Photos courtesy of Cambridge Historical Commission.

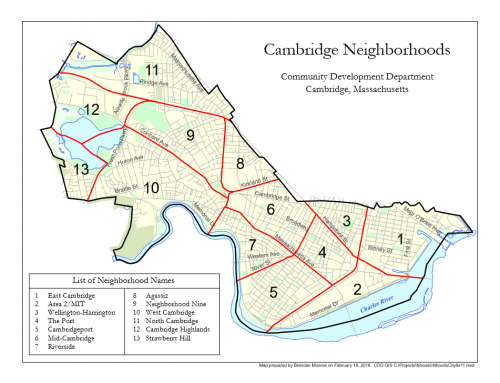

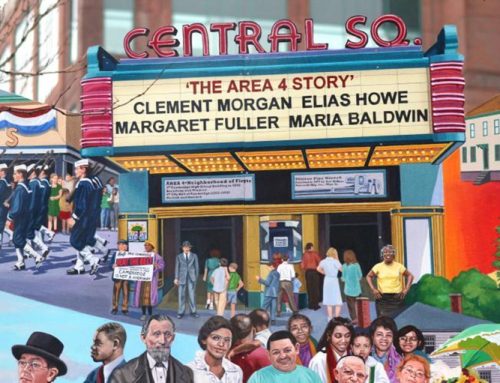

Black people have lived in this city since the late 1630s, when Cambridge was the “New Towne” across the river from Boston. Many were enslaved in Massachusetts until 1783. But the story of Black Cambridge is not simply about slavery; it also includes interaction and cultural exchange with Indigenous people. By the time the Civil War was over and the rest of the country had caught up with abolition, a Black middle class had emerged in Cambridge that included educators, businessmen, lecturers, and authors, as well as everyday residents who were building community through their churches, select small businesses, and fraternal orders like the Elks and Masons. An extraordinary — for the time — number of African Americans held appointed or elected positions, including common councilors, the fire chief, a city medical officer, a U.S. attorney, and others, from the 1870s through about 1900, when machine politics geared up and Woodrow Wilson segregated the federal service.

By the 1920s, Black residents — consisting not only of African Americans but also a large influx of Barbadians and Jamaicans who came seeking jobs — made up nearly 5 percent of Cambridge’s population. They resided largely in the lower Port neighborhood, in Central and Porter Squares, and along Walden Street between Richdale Avenue and Mead Street. The ensuing decades brought disruptive government-enforced housing segregation, including the 1938 razing of a low-income tenement neighborhood. In its place, two low-income housing developments were built side by side in the late 1930s to early 1940s, and they practiced segregation in housing assignments, with Newtowne Court primarily for white and Washington Elms for Black residents. As for the practice of redlining — the Federal Housing Administration’s refusal to insure mortgages in or near African American neighborhoods — it isn’t clear whether this widespread practice had as damaging an effect in Cambridge as it did elsewhere. In fact, Black home ownership was relatively high for a time, with many middle-class Black families owning their homes and establishing strong communities especially along Western and Concord Avenues.

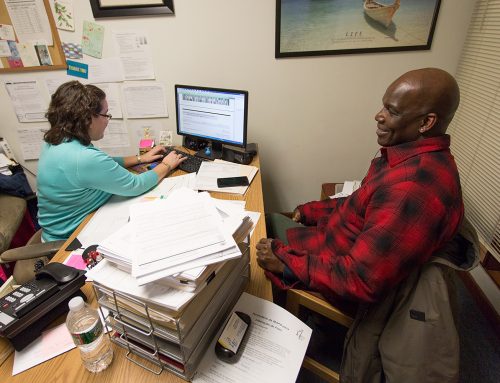

Today, Black residents are among Cambridge’s longest-term residents. More than a third have lived in their current home for a decade or more.

This is an excerpt from the Special Focus: The State of Black Cambridge, a chapter in our Equity & Innovation Cities research report. Read more here.

To take a deeper look at our city’s Black History, explore these great resources.