Published in The Boston Globe April 7, 2021 | By Andy Rosen, Globe staff

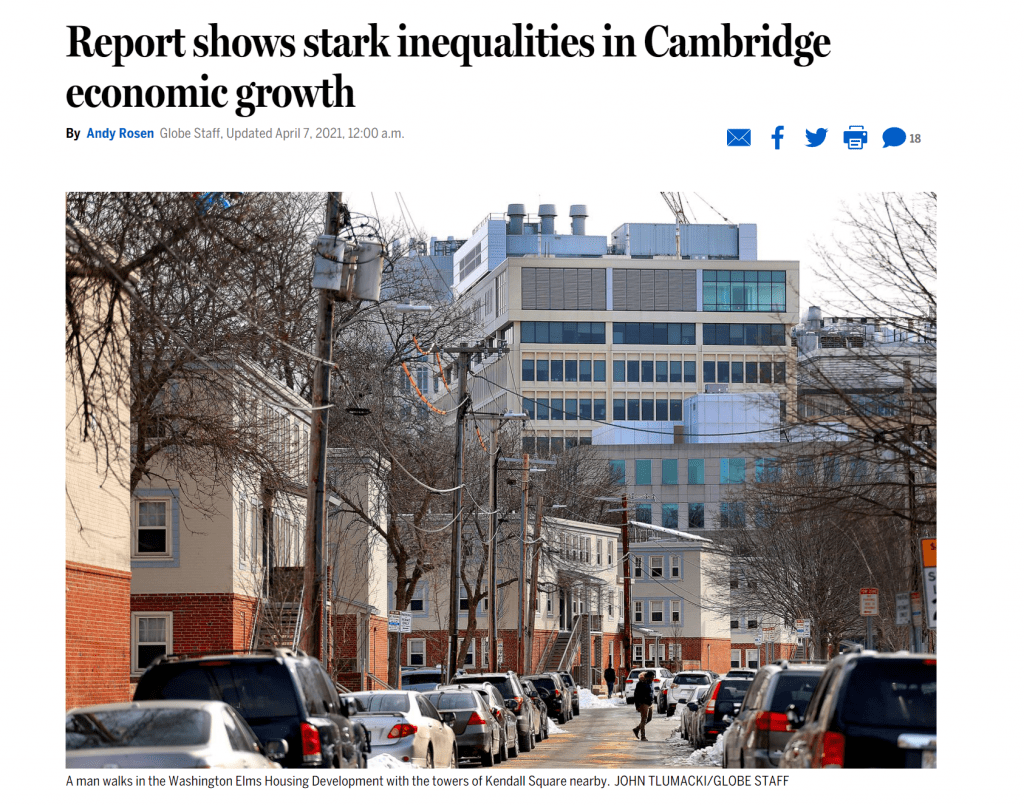

The report, scheduled to be released Wednesday by the Cambridge Community Foundation, highlights particular concerns for Black Cantabrigians, who have faced the heaviest burdens from the city’s high housing costs. Nearly one third of Black homeowners spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing, and 55 percent of Black renters do the same.

Those high costs are among several factors making it harder for longtime Cambridge families to stay in the city. The report found wide gaps in educational attainment among demographic and income groups, excluding many residents from the city’s robust innovation economy.

“The pandemic altered our lives in 2020, but the Cambridge we are waking up to today has been in the making for many years,” the report said. “Income inequality, the loss of the middle class, the closing of small businesses, ongoing gentrification, escalating housing costs, and deep racial disparities in education, wealth, and access to opportunity — these trends have been accelerating at least since the 2008 recession.”

Geeta Pradhan, president of the community foundation, said the report highlights one of the most frustrating — if promising — aspects of Cambridge civic life.

The city has fostered an inventive spirit that has led to breakthroughs including — most recently — Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine. But the community has not yet found a way to train its innovative faculties on the stubborn inequalities that plague many high-cost US cities.

“This is a place where people come from all over the world to solve problems, and we are solving amazing problems — like COVID. We are discovering new planets,” Pradhan said, noting that huge levels of wealth and investment money flow into Cambridge to support such work. “Surely, with the resources we have, with the power that we have, we should be able to solve the problems of our city.”

While Boston and Cambridge are often lumped together as part of a single metropolitan area, Pradhan said one of the goals of the report (which is based on data collected before the pandemic) was to isolate the specific economic factors at play in the smaller city.

It compared Cambridge with 25 other cities with economies that had enjoyed similar growth, “including established ones like San Francisco and Seattle, growing ones like Denver and Austin, and emerging ones like Nashville and Pittsburgh.” And it found Cambridge came out on top in some respects.

The city has more than 20 percent of adults working in an “innovation cluster occupation such as software development or biochemical research,” the report said — higher than any other area in the comparison.

But the report, citing US Census data, also found Cambridge also had the seventh-highest gap between the top 20 percent of earners, who had average household income of $343,000 annually, and the bottom 20 percent, whose income averaged $13,000.

The report also found that the city’s middle class, with an average household income of $95,000, is largely made up of millennial professionals who are more mobile and less likely to put down roots in Cambridge.

Meanwhile, Black residents make up only 8.4 percent of the population of people 25 to 34, though Black people account for 9 percent of the city overall.

The city is becoming more diverse as it grows — its population hit nearly 119,000 in 2018, approaching a high set in the 1950s. But while the number of Asian and Latino residents has increased as a percentage of the population over the past decade, the proportion of Black residents has dropped.