How many friends would you be willing to take a bullet for? Chances are, not many. But for Topper Carew, Tunney Lee was one.

“In the mid-1970s, a group of us were walking down 16th Street in D.C. when two white guys jumped out of the bushes and one of them pointed a gun at Tunney’s head,” recalls Carew, a director, screenwriter, and producer. “I jumped between the guy and Tunney and told the guy what I would do with that gun, and they were so stunned they ran away. That’s how deeply I felt about Tunney.”

Tunney Lee, a professor emeritus of urban planning and former head of MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning, died in July at 88. He was a friend of the Foundation, one of a group twenty exceptional artists, creatives, and innovators CCF named Cambridge Cultural Visionaries in 2020 for their rich contributions to cultural richness in our city and beyond.

Born in Taishan, China, Tunney was 7 when his father brought him to Boston to escape the Second Sino-Japanese War. He was largely raised by his grandparents in Chinatown; his grandfather had arrived in 1903 with his own father, who had worked on the railroads out west and in laundries in Bridgewater and Boston. “The whole community was very connected to China because of all the back and forth immigration,” says his daughter Kaela Lee, a retired dancer and professor of dance at College of the Holy Cross. “It was extremely formative for his psyche and his outlook on the world. The community was so small it was like being in a village.”

“It shaped his idea of what a neighborhood should be,” says his daughter Dara Lee Lewis, a cardiologist at Lown Cardiovascular Group. “Parents looking out for each other’s kids, newcomers welcomed, pedestrian friendly, kid friendly, educating, protecting, and supporting all the people who live in it.”

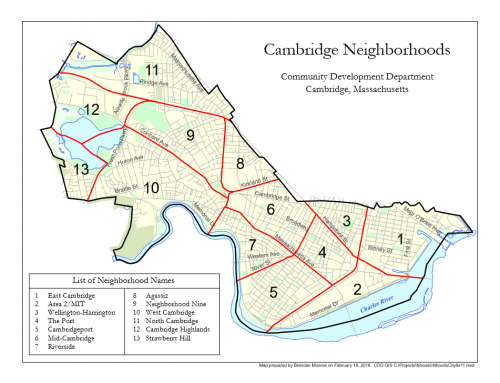

Tunney worked with giants in the field like Buckminster Fuller and I.M. Pei, and his ideas helped shape cities, including Cambridge. He was “instrumental,” according to Randall Imai, a principal at Imai Keller Moore in Watertown, in stopping the Inner Belt, a six-lane highway proposed in 1955 that would have cut through parts of Boston, Brookline, Cambridge, and Somerville. “Not only did he and [Mass. Secretary of Transportation] Fred Salvucci and a few others manage to stop that project,” says Imai, “but in 1970 Governor [Francis] Sargent put a moratorium on all freeway building in the Boston metro area.”

“That really would have changed the face of Cambridge,” says Antonio Di Mambro, a retired architect who studied with Tunney and later worked with him for many years in a firm they started together. “The whole city would have been restructured. He clearly had a social commitment and for him it was always people first. Not all architects are like that.”

Despite the magnitude of his work — he also had a hand in building or redeveloping public housing projects like Jefferson Park State on Rindge Avenue and World Habitat Award winner Tent City, on Dartmouth Street in Boston; helped start a school of architecture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong; won numerous awards, and sat on half a dozen boards — Tunney remained a “modest, humble, funny guy,” according to Imai. “The thing he emphasized was people.”

“He was never about making fancy pretty buildings for his ego,” says Kaela Lee. “It was always about serving people.”

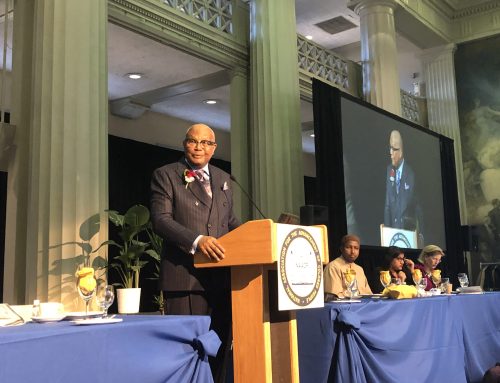

Cambridge Community Foundation president Geeta Pradhan sees the ripple effect left in Tunney’s wake, as city leaders work to create sustainable, human-scale buildings while still planning for future growth.

“Tunney was a creative thinker, a community builder, and an inspiration to us all,” she says. “His legacy will continue to inspire our community and the next generation of innovators and creators among us.”

We invite you to learn more about Tunney and his legacy, in Cambridge and far beyond, here.