“It’s not that easy being an artist,” says the attorney and writer Harvey Silverglate. But his wife, the photographer Elsa Dorfman, made it look easy, just as she seemed to do with every other aspect of her life.

“She was an alternative thinker in every possible way,” Silverglate continues. “But she was never a rebel or an angry person. She smiled and laughed a lot. She understood life could be difficult, but when she took pictures she got people to smile. She didn’t want to emphasize life’s tragedies.”

He recounts the time she got arrested for protecting her son’s friend from unnecessary treatment at a hospital by throwing a water glass at the doctor. When he went to see her, Silverglate says, “Elsa is sitting with the cops, laughing and having a good old time in the jail cell.”

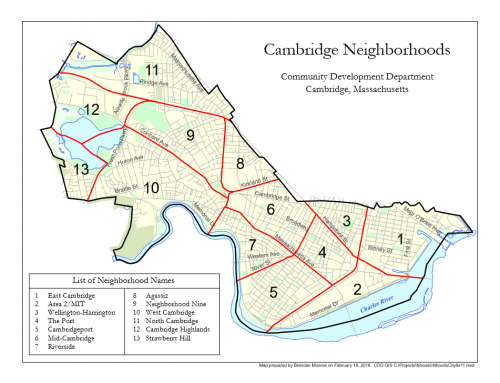

Like so many people from the community, the officers already knew Elsa, who died in May at age 83. Selected a Cultural Visionary in 2020 by the Cambridge Community Foundation for her contributions to the cultural richness of Cambridge, Elsa was also renowned for her intrinsic ability to connect and build community.

“She had the widest embrace of anyone I’ve ever known,” says the poet Gail Mazur, who first met Elsa when they were 9 years old. “She really, really loved people.”

Born in Cambridge, Elsa grew up in Roxbury and, after graduating from Tufts moved to New York City to take a job as a secretary at Grove Press, where she met Allen Ginsberg and the other Beat poets who would remain a part of her creative and social life for decades to come. When she returned to Boston to pursue her master’s in early childhood education at Boston College, she began arranging readings for her friends. “Her house was kind of like a salon,” recalls Silverglate.

Elsa quickly discovered she wasn’t cut out for teaching — “she didn’t like the strict rules,” Silverglate says — so when she got her first camera in 1965, he says, it was “love at first sight.” Early on she started taking her pictures to Harvard Square in a shopping cart to sell for $2.50 each. The hand-painted sign in the cart reading “singular opportunity” was perhaps tongue in cheek at the time, but, says Mazur, “those pictures are classics now. They’re in museums.”

By 1974 Elsa had published Elsa’s Housebook — A Woman’s Photojournal, which contained homey black and white pictures of her family and friends with handwritten captions such as “Robert Creeley talking to Fanny Howe. 1972.” So she was already making a name for herself when, in the late 1970s, the Polaroid Corp. built six 200-pound, 20-by-24-inch cameras that could create large format prints and she discovered the thing that would make her famous.

“Polaroid selected famous photographers to come to Cambridge and use the camera,” says Mazur. “She wasn’t famous, so they didn’t select her, but she selected herself.” She badgered the company, offering the two best prints in exchange for studio time, until they relented and allowed her to book the camera one day when Ginsberg and his partner, Peter Orlovsky, were in town. After that, she had it for one day a month until 1987, when she arranged to lease it and have it moved to her Cambridge studio.

Famous and everyday people posed for Elsa against a stark white backdrop in remarkably revealing portraits, often with family, pets, and objects they loved. The intimacy the photos convey, says Mazur, is a function of Elsa’s ability to “make everybody feel comfortable.”

And, like Elsa, the pictures were one of a kind. “She was a real original,” says photographer and social scientist Bobbie Norfleet, who is also counted among the Foundation’s 20 Cultural Visionaries and met Elsa shortly after moving to Cambridge in 1948.

“A lot of people you know are exactly like other people you know,” she continues. “Elsa was different. She was a true character. She was very funny, and said what she thought, which is not true of most people. She was passionate about the things she did. She didn’t do them because she ought to, or to become famous, but just because she loved doing them. You don’t meet many people like that.”

“Elsa’s life was shaped by creativity, passion, and empathy, and our community is richer for it,” says Geeta Pradhan, president of the Cambridge Community Foundation. “Hers is the kind of spirit that we want to see live on in Cambridge.”

We invite you to learn more about Elsa and her legacy, in Cambridge and far beyond, here.